Baby Bláithín O'Riordan, photo courtesy of her parents Natasha and Liam. All other photos by North West Newspix

An inquest into the death of baby Bláithín O’Riordan heard of the heartbreak of parents Natasha and Liam as their beautiful little girl passed away shortly after her birth.

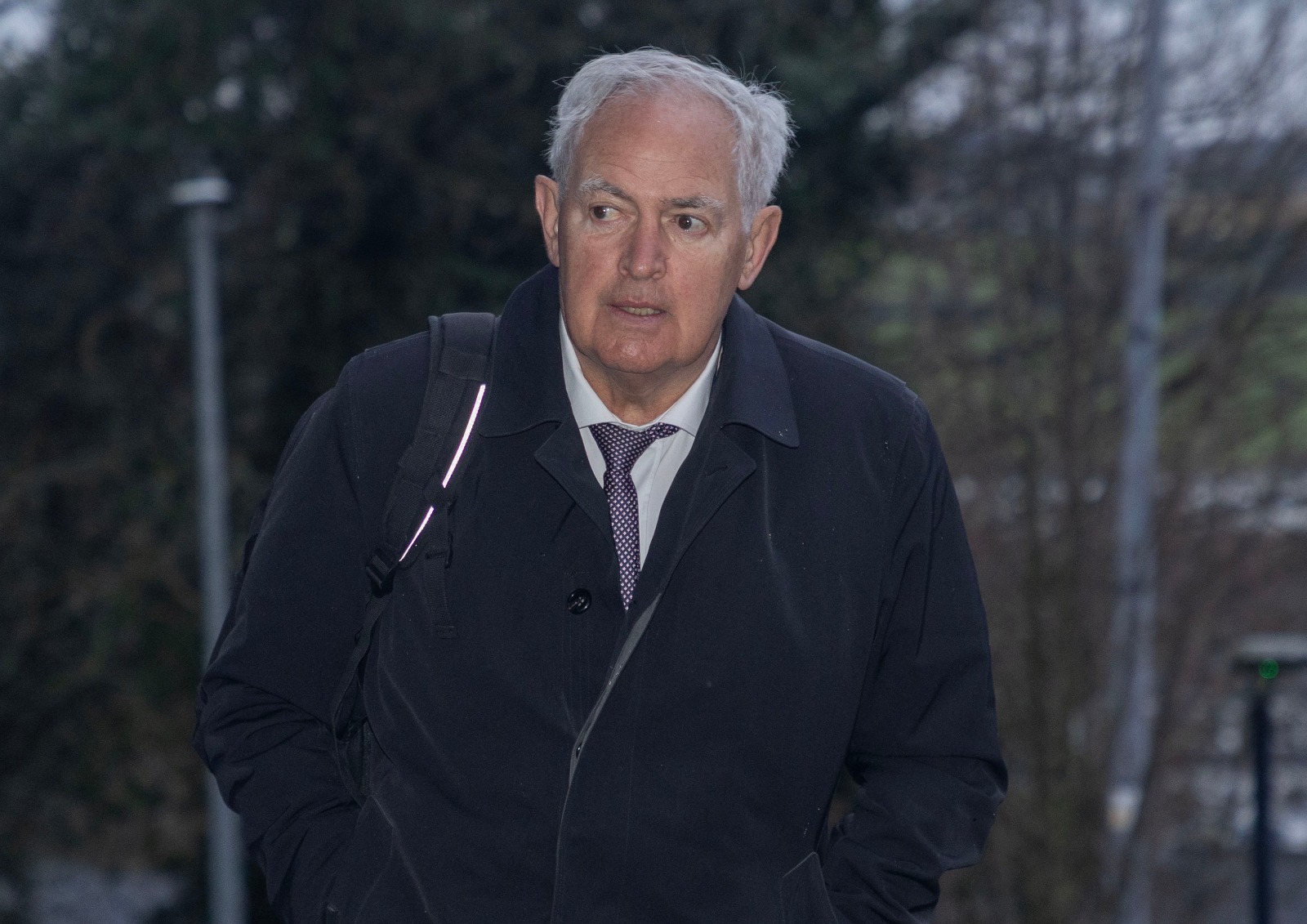

The inquest at Letterkenny Courthouse was presided over by Donegal coroner Dr Denis McCauley, who returned a narrative finding rather than one of medical misadventure or natural causes as sought by respective legal teams.

Bláithín was born at Letterkenny University Hospital (LUH) at 6.56am on February 4, 2023, and tragically, was pronounced dead at 8.02am.

The two-day inquest opened on Tuesday, January 27 and concluded after 9pm on Wednesday, January 28. Depositions and evidence were heard from 16 witnesses, including Bláithín’s parents Natasha and Liam, medical experts, and hospital staff involved in the care of Natasha and Bláithín. This was followed by submissions from Damian Tansey SC briefed by Aisling Harrison, representing Natasha and Liam O’Riordan, and Luán Ó Braonáin SC Senior Council briefed by VP McMullin on the instruction of the State Claims Agency for LUH.

Narrative Finding

Having considered the evidence and points raised in the submissions, Donegal coroner Dr Denis McCauley returned the following narrative finding: “Blátihín was born on February 4, 2023 at term and four days. She died within an hour of birth. She had aspirated meconium. At five minutes of life her heart had stopped.

“Post-mortem examination revealed extensive placental disease impeding oxygen exchange. This had caused widespread chronic ischaemic brain injury that predated the onset of labour by at least seven days. There was also fatal acute brain injury that occurred at least six hours before Blátihín’s birth, when the placenta was no longer able to cater for Blátihín’s perfusion needs towards the end of pregnancy and during labour.

“During the initial resuscitation, there was an issue with the component of the resuscitation equipment that allows for increase of IPPV pressure, resolved over a minute and a half. During a period of the first intubation, the CO2 monitor was negative.”

Evidence

Evidence heard on day one outlined panic in the delivery room within moments of Bláithín’s birth, and the fear and devastation for Natasha and Liam as their precious dream turned to a nightmare.

In the afternoon of day one and into day two, medical staff at LUH documented the events from Natasha being admitted to hospital to the labour and birth, to the realisation that something was terribly wrong and all that ensued.

The couple discovered the previous May that their latest IVF treatment had been successful and that they were expecting a baby. At the 20-week scan everything was perfect, Natasha said in her deposition which she courageously read to the inquest.

“On February 2, 2023, my blood pressure was slightly elevated,” she outlined. “It was decided I would be induced the next day.”

A pessary was inserted the following day to induce labour. Checks and scans were performed, and everything seemed fine.

Just before 11pm, contractions became regular. A consultant was informed.

Natasha was in need of pain relief, and the consultant instructed that she be brought to the labour ward with the pessary still in place.

“I thought this was very dangerous,” said Natasha. “The midwife told him it was not protocol.”

He said he would remove it but it was not his recommendation.

“He did it; it was very rough and it felt like his hands were in my abdomen,” recalled Natasha.

She was taken to the labour ward and it was noted that her blood pressure was elevated. Natasha opted for an epidural, and rang Liam who came to join her.

“A while later I began to feel pressure and began to push,” she said. “The head was visible.

“I could feel Bláithín moving, I placed my hand on her head and could feel it moving.

“The happiness and joy in the room was palpable. When Bláithín was placed on my chest it felt like all my dreams had come true.”

A short time later the registrar was called. Bláithín was displaying signs of being a ‘shocked baby; with wide eyes and arms outstretched. Natasha had seen this before and was not overly concerned until Liam said something was terribly wrong.

The resuscitation equipment, known as a resuscitaire, wasn’t working. Natasha’s midwifery experience kicked in.

“I asked if they could take a resuscitaire from another ward,” she said.

Liam, a member of An Garda Síochcana, described scenes of panic.

Efforts to intubate Bláithín failed. Natasha appealed for those present to use the bag and mask resuscitation method but this was not done.

“It was sheer panic, nobody really knowing what to do,” said Natasha. “The most important person in the room didn’t get a chance.”

An off-duty consultant, Dr Asim Khan, was called. He arrived around 35 minutes later and took charge, performing the intubation without further delay.

Liam shared the difficult conversations that he had with family members at this point.

“I called my mother and Natasha’s brother and told them a baby girl was born but that she probably wasn’t going to make it,” he said.

Despite Dr Khan’s efforts, Bláithín could not be resuscitated.

“After it stopped, they laid her skin to skin on my chest,” said Natasha. “All our hopes and dreams had been shattered. We dreamed of holding our baby in our arms but never could we have imagined this nightmare.”

The couple got to spend time with their daughter before she was brought to Galway for a post mortem examination.

Perinatal pathologist Dr Laura Aalto (pictured below) told the inquest that there was no way to tell if a shortage of oxygen (hypoxia) or blood (ischaemia) to the brain had occurred during labour and immediately after Bláithín was born. However, she did discover factors which contributed to the death.

The major issue was with a fibrinoid in the centre area of the placenta compromising Bláithín’s oxygen and blood supply to the brain.

“A fibrinoid is a substance that is made during an inflammatory reaction,” explained Dr Aalto.

This had caused injury to the brain, with indicators that it had begun a week beforehand. It severely affected Bláithín’s ability to get the extra oxygen that she needed for labour and birth.

There was also evidence of a more recent acute hypoxia and ischaemia, which the pathologist said would have occurred before labour began.

Furthermore, there was evidence in the lungs of meconium, a waste substance composed of materials ingested by the infant in the uterus and which is usually expelled after birth. This happened in tandem with what appeared to be reduced liquor, the amniotic fluid which cushions and nourishes the foetus in the womb. The foetus reflexively swallows and inhales amniotic fluid as part of its healthy development.

Dr Aalto recorded her findings on the cause of death as: “Critical hypoxic ischaemic multiorgan injury, acute on chronic, occurring on a background of placental pathology with marked fibrinoid deposition and acute chorioamnionitis, complicated by fetal pulmonary inflammatory response and meconium aspiration.”

Over the course of the next day and a half, those involved in Natasha and Bláithín’s medical care gave evidence and answered questions from the coroner and legal representatives.

There was much discussion regarding the sensitivity of the tests and scans, and why the problems with the placenta had not come to light.

Had this happened earlier in the pregnancy, the inquest heard, the placenta might have been smaller than would be expected and this would have been noticed. But because the placenta was fully formed when the fibrinoid developed, the damage was only detected under the microscope during the post mortem examination.

Questions were asked as to why, given that this was an IVF pregnancy preceded by a miscarriage, it was not classed as high-risk. Medical professionals and expert witnesses responded that those were not factors which, in isolation, would lead to such classification.

It was established that Natasha had elevated blood pressure late in pregnancy, but not pre-eclampsia. This was enough to increase the risk classification, influencing the decision to induce labour which in turn raised the risk factor. However, evidence was given there were no indications for a caesarean section to be carried out.

It had been noted that while Natasha had, in an earlier consultation with her obstetrician, expressed a preference for a natural delivery. However, she accepted that intervention could take place if there were robust reasons for doing so.

There was much discussion regarding a change in fetal heartbeat approximately an hour before delivery, with mixed opinions from medical professionals and expert witnesses on whether this should have prompted emergency intervention.

Mr Tansey said Natasha was haunted by this, and would always wonder if intervention would have led to a better outcome.

Witnesses said that the heartbeat had subsequently returned to an expected rate, quelling any concerns. However, it was noted that this information had not been passed on to Natasha’s obstetrician, a fact which he said was ‘disappointing.’

During delivery, vacuum suction was used on Bláithín’s head due to the ‘push’ stage being prolonged by more than an hour. This, the inquest heard, is protocol when the mother has had an epidural. The process was described as ‘successful’ given that the baby was then delivered in three pushes.

Staff were asked why a foetal scalp electrode was not applied as this would have given an indication of the baby’s heartbeat. The inquest heard that it was not deemed necessary.

A factor raised by Mr Tansey was that at one minute old, Bláithín had an Apgar score of five out of ten. The Apgar score indicates the baby’s health at birth and is based on the five vital signs of colour, heart rate, reflexes, muscle tone, and respiration. Mr Tansey put it to the healthcare professionals that it would be ‘very rare’ for a baby with an Apgar score of five not to survive.

By five minutes old, when the assessment was repeated, the Apgar score had dropped to one.

It was acknowledged that it was unusual for a baby not to survive, but that the Apgar score was a snapshot used for guidance and not a complete indicator of the baby’s health.

Those present were questioned in regard to the methods and protocols used in the efforts to resuscitate Bláithín.

Doctors denied that it had been chaotic, stating instead that it was an emergency situation and the response was ‘urgent’ rather than panicked.

It was acknowledged that the resuscitaire equipment had not worked properly in that the capacity of air being pumped into the lungs could not be increased. Doctors described getting a machine from another room, leading to a delay of around 90 seconds during which time resuscitation at the lower rate continued.

While they acknowledged that the bag and mask method had not been applied, it was said that other alternatives were used.

The inquest heard of various attempts to intubate Bláithín, and the uncertainty as to whether intubation had been successful. Potential blockages and the absence of a heartbeat after the first five minutes meant that the CO2 indicator which would have shown that the tube had reached the airway did not activate.

Dr Khan, the off-duty consultant who was called from his home, said he had been satisfied that his intubation had been successful because he could see the rise and fall of the chest cavity.

All those who gave evidence to the inquest expressed their condolences to Bláithín’s parents Natasha and Liam.

Submissions

Both barristers made submissions to the coroner once all evidence was heard.

Mr Tansey outlined the circumstances surrounding the pregnancy, labour and delivery, making reference to Natasha’s exceptional care and vigilance.

“She was coming to the end of the pregnancy, the best part, the part that produces this miracle, the child Bláithín,” said Mr Tansey.

“You heard about the discussions she had with the consultant - if there is any robust indicator to bring forward the birth date, she would follow that advice. We know that didn’t happen.”

Mr Tansey referred to evidence by professional witness Dr Peter Boylan, former Master of the National Maternity Hospital.

Dr Boylan explained that CTG machines which monitor the fetal heart rate are useful in that they are reassuring when everything is going well, but can cause ‘false negatives’ as to whether there is a problem. More often than not when a potential problem is indicated, there is in fact, no issue.

Mr Tansey said the doctor has indicated that the monitor was less than perfect and there were other tests such as the doppler and ultrasound scans.

“The various tests showed that all was in order,” said Mr Tansey. “Natasha and Liam were anticipating the miracle that would arrive and did arrive.”

Mr Tansey told the inquest that Natasha and Liam had expressed concern that the situation was made worse by the fact that it happened over a bank holiday weekend, that the paediatrician was a locum and the registrar was a new appointment.

He raised questions about the adherence to protocol, to ‘the golden standard’ of which the most important step is to ventilate the baby’s lungs first.

“That didn’t happen,” he said.

“We heard powerful evidence from the last witness [Dr Khan] that timing is everything.

“If you don’t see results in 30 seconds you must adopt an alternative method.”

He reiterated the various shortcomings of the equipment and the failed or uncertain attempts to intubate Bláithín, and prior to that, the lack of intervention when the fetal heartbeat had dropped for a period at 5.30pm.

The barrister acknowledged that Bláithín had suffered from hypoxia and ischemia in the week prior to her birth, but said this was not a death sentence.

“The extent that it would have impacted on her development is another matter, but she would have survived,” he said.

“That is the issue in this inquest - if she would have survived and the fact that she didn’t survive.

“I would suggest you should return a verdict of medical misadventure.

Mr Ó Braonáin stressed that it was not the purpose of the inquest to either blame or exonerate, and he questioned the language of Mr Tansey in that context.

“Medical misadventure does not mean medical negligence,” he added.

Mr Ó Braonáin drew attention to the findings of the pathologist.

“The injury was caused long before the delivery and it remained silent,” he said.

The barrister recalled the pathologist’s evidence that the demands during labour would have been critical, with the placenta unable to support the foetus in the manner that was required.

He added that Mr Boylan, having reviewed the notes from the hospital, said in his report that death was unavoidable.

“There is a line drawn clearly from the condition to the death,” said Mr Ó Braonáin. “Where there is a condition and medical intervention fails to fix it, it is the condition that is the cause of death.

“I think that a verdict of natural causes would be well founded on the evidence.”

The barrister added: “No-one in this room is anything but affected by the outcome for Bláithín and there is nothing but sadness in relation to that.”

Conclusion

Dr McCauley said that in considering the facts and coming to a finding, there were three concerns: the positive antenatal tests, the labour itself, and the resuscitation. He accepted the pathologist’s timeframe for the placenta problems, and that the equipment simply could not have detected it.

“Her placenta wasn’t well,” he said. “She was about to be exposed to a physiological assault even if it was a perfect labour.”

However, Dr McCauley added: “It is unlikely that the histological findings were enough to cause Bláithín’s death. Other things could have happened during labour that we can't prove or disprove. “But there was an awful risk to Bláithín going into labour, one that you could never have known.”

Regarding the variation in heartbeat at 5.30am, Dr McCauley said: “The midwife noticed this event and then tested that event.”

He said there was no evidence that this event should have led to further intervention.

The coroner outlined Bláithín’s poor health at the time of delivery.

He said that Bláithín’s heart had stopped after five minutes, and the initial response was appropriate. While there were problems with the resuscitaire, oxygen was given while finding a replacement.

The conflict lay in whether an early successful intubation could have saved Bláithín.

“If it had been put into place and the CO2 detection was positive, we all would have been reassured,” said Dr McCauley. “But there is an element of doubt.”

In returning a narrative finding the coroner expressed his condolences to the family and he said he hoped that the inquest had served the purpose of answering their questions.

Recommendations

Dr McCauley added that he would be writing to the HSE to express two recommendations arising from the inquest.

-1770222922806.jpg)

The first related to a review of the diagnosis of the onset of labour. He and the expert witness had concerns that there are no obvious guidelines in relation to frequency of monitoring of women, and particularly their baby in their first pregnancy when they are having significant regular uterine contractions and the neck of the womb is shortening but cervical dilatation has not started.

"An inquest we heard that the monitoring of the fetal heart during this period is very arbitrary and can be between every four hours or every hour rather than continuously when the cervix reaches a particular level of dilatation,” he said.

The second recommendation relates to amniotic fluid.

“It is important that during labour when amniotic liquor drainage is being assessed, if it is deemed to be absent or indeed low in volume, it should prompt a reassessment of the present clinical condition of the baby. This should occur even when antenatal scans indicate reassuring amniotic fluid volume.”

Speaking after the inquest, Natasha and Liam said the inquest had given some but not all of the answers they sought.

Natasha said their concerns had been vindicated last year when the High Court ruled in their favour.

Subscribe or register today to discover more from DonegalLive.ie

Buy the e-paper of the Donegal Democrat, Donegal People's Press, Donegal Post and Inish Times here for instant access to Donegal's premier news titles.

Keep up with the latest news from Donegal with our daily newsletter featuring the most important stories of the day delivered to your inbox every evening at 5pm.