Seamas Sharkey at the Diamond, Donegal Town, last month

"Get up Sharkey. Get up Sharkey. If you were any good you would get up and hit me, but you aren’t any good."

Those were the intimidatory taunting words of a bullying schoolmaster at Ard Scoil Mhuire, Gaoth Dobhair, in 1965, after he floored 12-year-old Seamas Sharkey from Carrickfinn with a solid punch on his first week at the school. It marked the beginning of five torturous years of secondary education, lasting until the Leaving Certificate of 1970. Seamas never found out how he did in the exam, because he didn’t hang around to find out.

It was the long-haired 1960s fashion. Once a month, the barber arrived to keep pupils in check. Tired of having his hair cut, Seamas missed one trimming. The following day, he was called outside by the school chaplain and ordered to explain his absence.

READ NEXT: From the hills of Glenswilly to 40 metres below England’s earth

After explaining he had been ill, he was first suspended and then punched until his nose bled. He walked all the way from Bunbeg to Mullaghduff. Shortly after being reinstated, he was then told to fix a teacher’s puncture. When he refused, he was again punched to the floor and suspended.

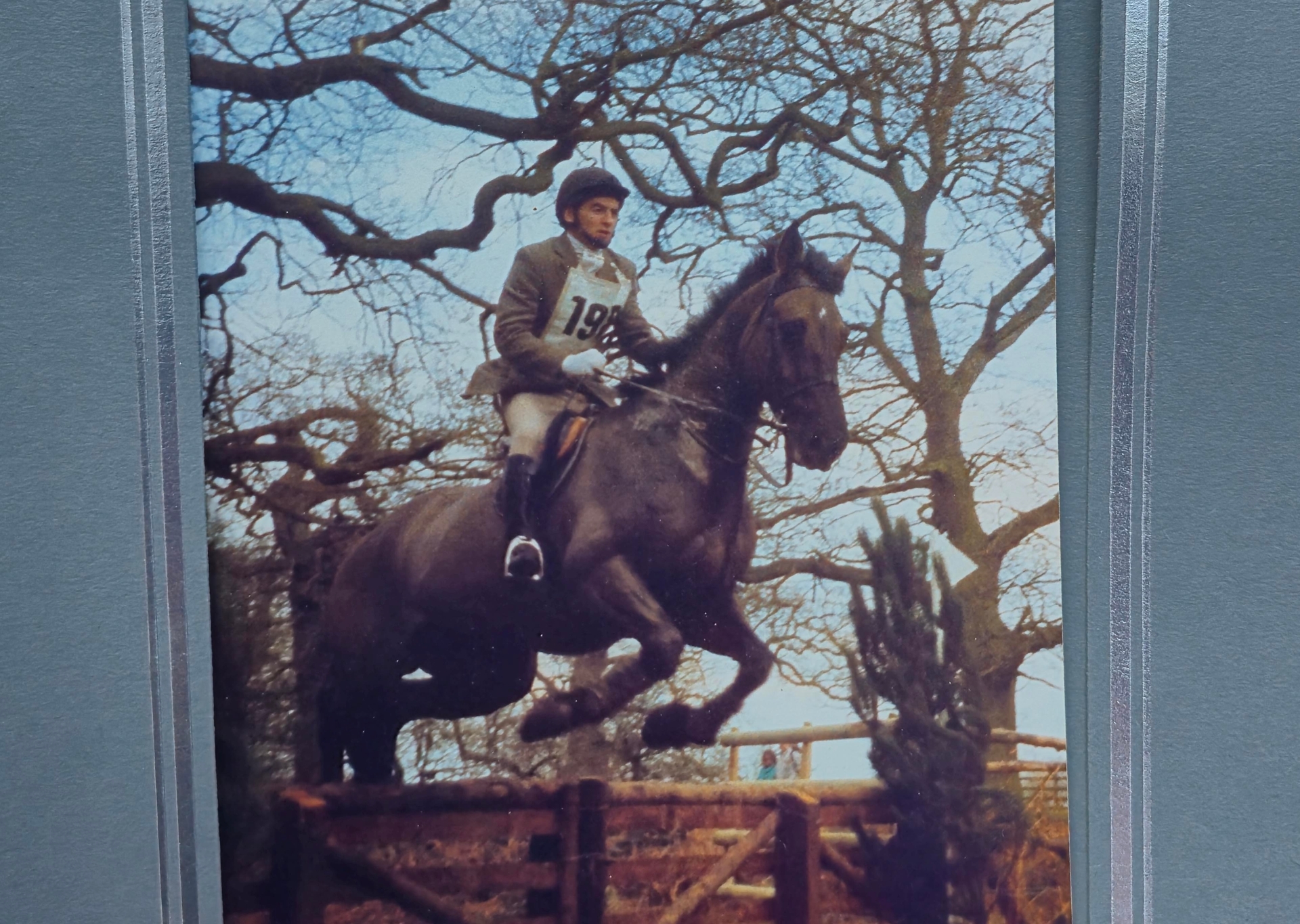

Seamas riding his per horse, in Leeds in the 1970's

The brutality had started earlier, at Mullaghduff Primary School in 1957. On his first day the teacher told him she would spank him, and true to her words, she repeatedly did.

Although Seamas later became known for his underground tiger tunnelling, he still wonders how he survived school long enough to ever see a tunnel face.

£30 Savings, Leeds, and the Road Underground

After the Leaving Certificate, he withdrew his savings, £30 from Annagry Post Office, and headed for Leeds. He stayed with family friend Donal Boyle. Seamas’s father had been a handyman and from an early age Seamas learned to use tools. He secured work in Leeds as a shuttering carpenter. Soon, he heard of a major project back in Ireland at Turlough Hill, County Wicklow.

The Turlough Hill pumped storage hydro station was a major ESB project. It involved driving tunnels through the mountain to a reservoir at the summit. Water was pumped uphill at off-peak times and released during peak demand to drive turbines. As a shuttering carpenter earning £120 per week, Seamas worked on reinforced concrete structures.

On that particular project, carpenters were earning more than tunnellers. One unnamed Donegal carpenter transferred to tunnelling while retaining carpenter’s pay. A union meeting was called by disgruntled Jackeen workers. The Donegal man slammed his fist on the table, declaring that “no culchie would be demoted or suspended from the hill”. The meeting ended and work continued unchanged.

A Tunnelling Apprenticeship

When Turlough Hill finished, Seamas returned to Leeds in 1973 and entered tunnelling. He began on timber heading tunnels, a two-man operation involving manual air spade excavation, rail-mounted skips, and timber supports. Concrete pipes were laid and encased, all by hand. When groundwater was encountered, two sets of clothes were needed, one worn and one drying on the compressor. During periods of heavy groundwater inflow, Seamas and Donal Boyle went through three changes per shift. When asked how that felt, Seamas quickly retorted as “cruel”.

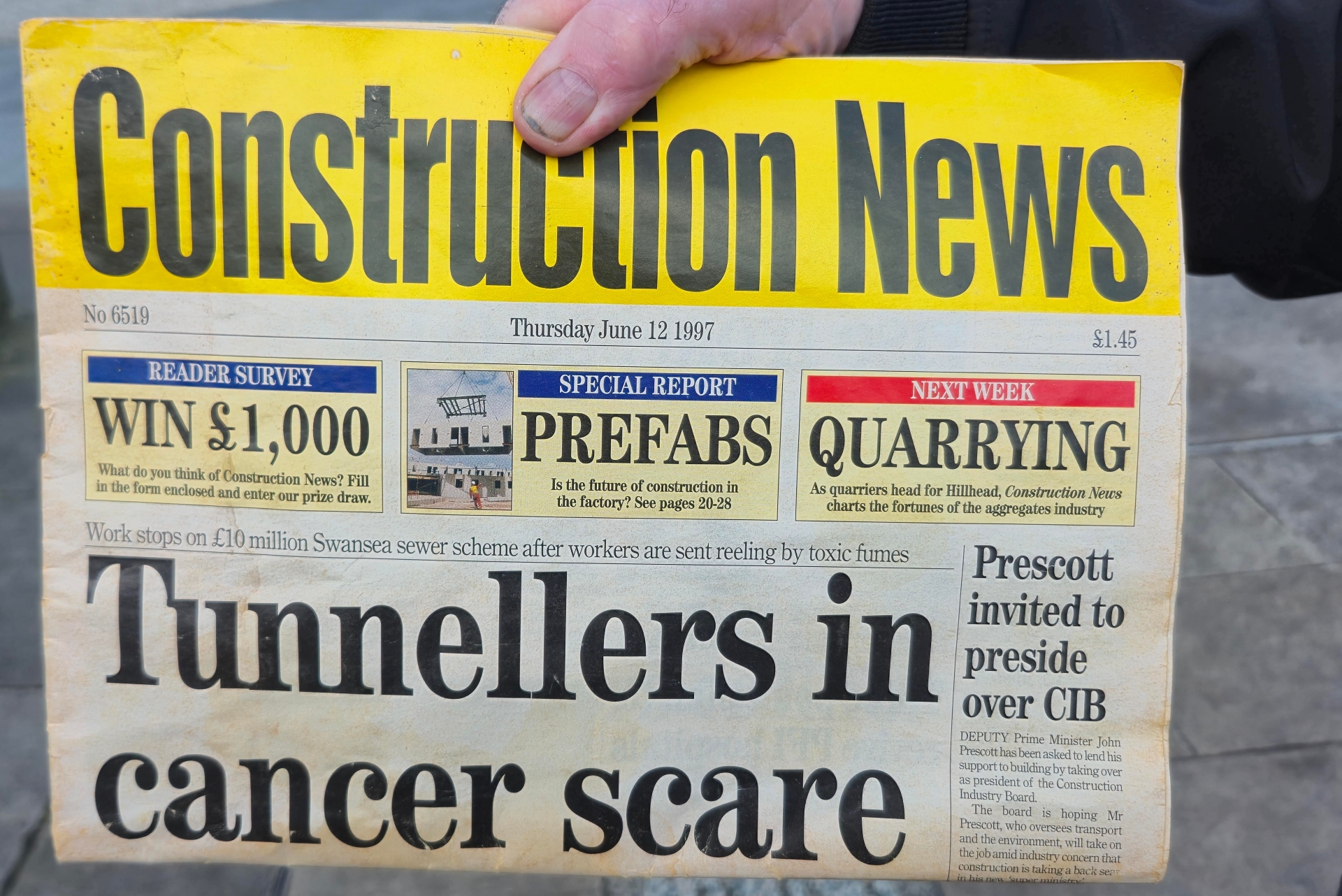

Construction News Front Page June 1997

One Friday evening, climbing out of a 30-foot shaft, he slipped and fell back to the bottom, his ankle shattered. Because it was a Friday evening, the crane was locked away. Hence, two concerned tunnellers lowered a rope from the surface. Down at the bottom of the shaft, Donal Boyle tied it around Seamas’s waist. The two men then hauled from above while Donal pushed from below all the way up the 30-foot-tall ladder. For six weeks, his ankle was restrained in weighted traction, repeatedly dragging him out of bed. Steel rods were then inserted, and the overall recovery took five months, a period during which Seamus did not earn any wages.

Rock, Explosives, and Near-Death Experiences

In 1977, aged 27, Seamas moved into rock drilling and blasting at Stockton. Holes were drilled through the rock, packed with gelignite, blasted, and cleared. Dangerously, the tunnel was permanently filled with natural gas and gelignite residue. Overall, the air was poisonous. Seamas collapsed and was rushed to the hospital, where he later regained consciousness. Doctors told his wife he was close to a heart attack. Against medical advice, Seamas signed himself out and returned to work on Monday, where he witnessed large numbers of other tunnellers collapsing around him in the same poisoned conditions.

In 1978 he moved to Telford. Uncertified tunnellers were barred from handling explosives, so a supposedly munitions expert was hired. On his first blast, he totally miscalculated and blew out tunnel lining supports right back to the shaft. Highly embarrassed, he then sheepishly asked Seamas to take over the explosives. Weeks later, with a broken drill and no drilled holes, Seamas had to take the explosives home. On the way, he stopped at a supermarket. A bomb scare was announced and the building was evacuated. Army and police swarmed the area. Seamas, thinking himself the prime culprit, walked nervously towards his car, waiting for a tap on the shoulder. Fortunately, he wasn’t stopped or searched. He believes that had he been searched, he would still be in a British prison, albeit through no fault of his own.

After Telford, he moved to Selby, sinking 700-metre shafts for the Coal Board. There, he joined the German firm Thyssen and entered a pension scheme that later proved invaluable. With Thyssen, he continued drilling and blasting through frozen ground and rock, work that, when combined with previous drill and blast operations, left him permanently deaf with related respiratory damage. At one stage, at the base of a deep shaft, a grab operator swung a mechanical grab so close it knocked the battery pack from Seamas’s body. Four inches closer would have killed him. On the same project, a plumb bob fell from the top of the shaft, killing a fellow tunneller instantly.

Seamas Sharkey and Eamonn Coyle in Donegal Town, where they spoke

The Channel Tunnel, Deafened but Still Driven

In 1989, Seamas headed for the Channel Tunnel. A medical rejected him due to hearing loss. However, his supervisor, Frank Cordiff, kindly intervened, stating he preferred deaf men because they were experienced, reliable and skilled. Seamas worked on the air release piston shafts between the main tunnels. Despite mechanisation, his work remained manual, using German Gigger air spades. The shafts were driven through hard rock without explosives. At one point a superstitious rumour spread that the tunnel would collapse. Combined with timely heavy groundwater ingress, many workers stayed away. Fortunately, the collapse never materialised.

Heathrow Express, Where Speed Trumped Safety

In 1995 Seamas worked on the Heathrow to Kings Cross Express line. Productivity ruled. Corners were cut. Shotcrete linings were applied but not given proper curing time. One day the guidance laser began to drift. Closer investigations revealed that it wasn’t the laser moving at all but the tunnel itself! In a state of panic, all operatives immediately evacuated. Three tunnels collapsed, bringing the streets and buildings above into the void. Fortunately, no tunneller was injured, but the incident caused public outcry, gained international media attention and caused huge embarrassment for the main contractor.

READ NEXT: The Donegal man who was buried alive at the tunnel face and lived to tell the tale

Poison Air and the Impossible Job That Could Not Continue

In 1997 Seamas went to Swansea, drilling a six-foot tunnel through highly contaminated ground. Toxin levels were so high that tunnellers became punch drunk. The air was also carcinogenic.

Medical tests showed Seamas’s benzene levels at 1,200% above safe limits. The job was shut down and made it onto the front pages of the industry’s main journal, Construction News. He later worked on several other projects, including sewer pipe jacking at St Andrews, the home of golf.

Early Retirement Earned, at a Permanent Cost

Seamas retired in 2010 at the age of fifty-seven, having earned enough to step away early and on his own terms. He built a home in Braade, Kincasslagh, County Donegal, where life now moves at a slower, quieter pace. He spends his time with his wife Rose, fishes out of Carrickfinn harbour, keeps sheep, and tends to the land. Together, he and his wife travel abroad two to three times each year. They also visit their married son in England.

During his working life, he invested in property in England, owned horses, and took pride in training and riding them.

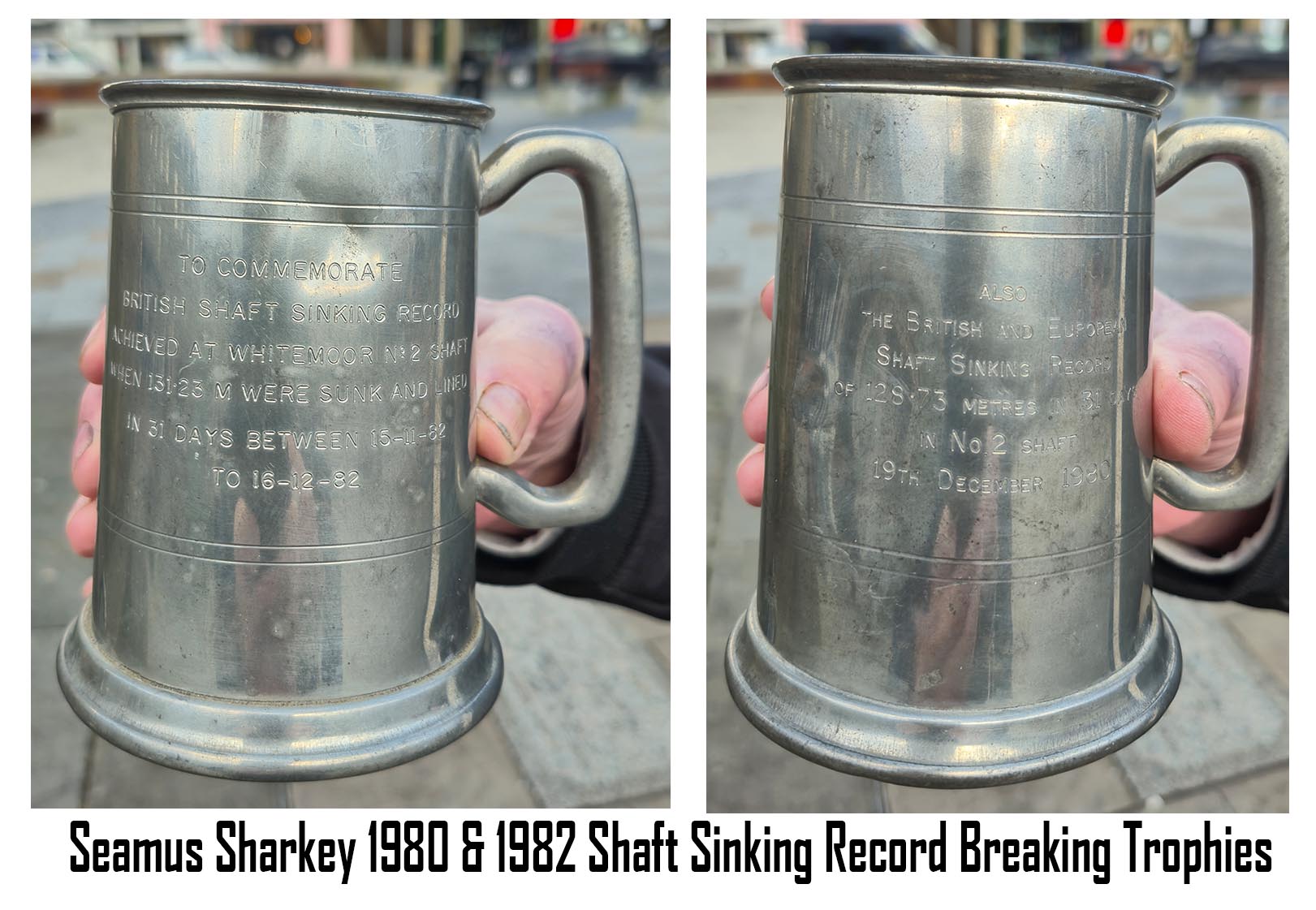

Asked if he would do it all again, Seamas does not hesitate. He would choose tunnelling every time. It hardened him, gave him independence, and bought him his freedom years earlier than most. During his shaft sinking operations his team set two world records and was presented with prizes which he dearly hangs onto to this present day.

The price of tunnelling, however, was unforgiving. He lives with permanent deafness and relies on respiratory support, the physical legacy of decades underground.

He ends with a reminder. This story may chart a life spent driving tunnels through rock, but it must also record the damage done long before that, in classrooms rather than shafts. The torture endured at school, particularly at Ard Scoil Mhuire in Gaoth Dobhair, shaped the man more significantly than any blast or collapse.

Seamas is a fluent Irish speaker, and much of his account was given as Gaeilge, the language in which many of those memories still live.

Eamonn Coyle is a Chartered Engineer and Chartered Environmentalist

Subscribe or register today to discover more from DonegalLive.ie

Buy the e-paper of the Donegal Democrat, Donegal People's Press, Donegal Post and Inish Times here for instant access to Donegal's premier news titles.

Keep up with the latest news from Donegal with our daily newsletter featuring the most important stories of the day delivered to your inbox every evening at 5pm.